Glossary of terms

The Public Waterfront Act

The Public Waterfront Act—also known as Chapter 91 of the Massachusetts General Laws, or just “Chapter 91”—gives every Massachusetts resident a legal right access and use tidelands, which are held in public trust by the State's Department of Environmental Protection. The law rests on the Public Trust Doctrine, a longstanding common law principle that natural resources like the air, rivers, sea, and shores should be held in trust by the government for public use and enjoyment.

The Public Waterfront Act specifies the following requirements for non-water-dependent uses on private and Commonwealth tidelands

- Minimum public open space. At least 50% of the site must be dedicated to open space.

- Lateral Shoreline Access Requirements. The site must provide lateral accessways that connects the shoreline to public ways.

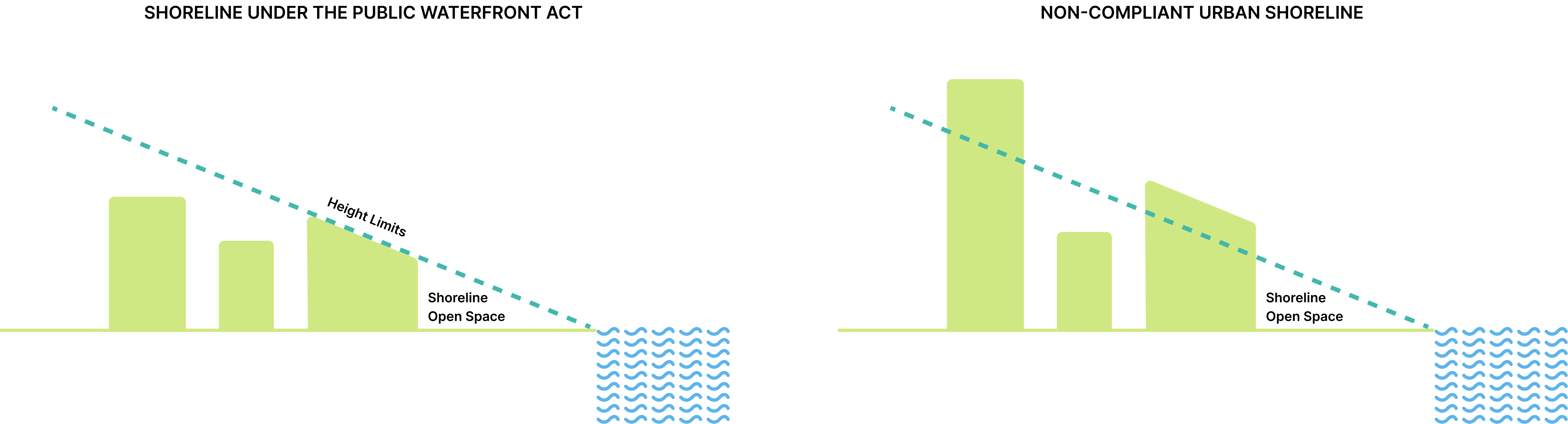

- Maximum Building Heights and Setbacks. Buildings within 100 feet of shoreline are limited to 55 FT in height. Beyond 100 feet of the shoreline, building height may increase 1 foot per every 2 feet of distance further inland from the shoreline. (Substitutions to maximum height requirements typically allow a project to hit a new maximum height level across the site, as opposed to altering the numerator or denominator of the setback ratio.)

- Signage. The site must include signs detailing facilities of public accommodation (FPA) and waterways license information.

The Act specifies the following more intensive requirements for non-water-dependent uses on Commonwealth tidelands only:

- Pedestrian Amenities. The project must provide basic public amenities for exterior public spaces: lighting, seating, restrooms, trash cans, etc.

- Interior Public Space. 75% of rentable ground floor space should be dedicated to Facilities of Public Accommodation (FPAs).

- Pedestrian Amenities. The project owner must maintain and enact a plan for providing other public benefits and publicly accessible programming for all Facilities of Public Accommodation (FPAs).

*Because they exert a de minimus impact on project value, the tideland development calculator does not model the impact of the signage requirement (#4) or the management planning requirement (#7) on projects.

Municipal Harbor Plan

A long-term planning and development vision for multiple, connected harbor-front sites. These plans provide cities and towns with some flexibility in how they develop waterfront areas, as long as they do not compromise the area’s overall public benefits.

Tidelands

Tidelands are land or tidal flats located below the high-water mark, either currently or in the past. Tidelands fall into several categories, including Commonwealth tidelands and private tidelands.

- Commonwealth tidelands are currently or historically seaward of the mean low-water line. The public’s trust rights in these tidelands require the most significant standards for the quantity and quality of public access, including programming to attract the community to the waterfront.

- Private tidelands exist between the mean low-tide and mean high-tide marks. The public holds a permanent easement on these lands, even if they’ve been filled in since they were conveyed to private owners in the 1600s. These tidelands carry fewer requirements for public access and benefits compared to Commonwealth tidelands.

Facilities of Public Accommodation (FPA)

Uses where goods and services are regularly available to the public on equal terms. Examples of FPAs include restaurants, performance areas, hotels, retail spaces, and educational and cultural institutions.

Financial Mitigation

Financial compensation paid by a project owner to the public in return for an imposition on the public’s right to access the waterfront. Financial mitigation is uncommon, and it is only required when a municipal harbor plan make “substitutions” (changes) that relax one or more Public Waterfront Act requirements and it is impossible for the project owner to offset those substitutions by creating publicly accessible waterfront area elsewhere onsite, such that net quantity of public access does not change.

Water-dependent use

Uses and structures that require direct access to, or location in, the water to function. Examples include marinas, ferries for water transportation, piers, wharves, and shoreline protection.

Non-water-dependent use

Uses and structures that do not require access to the water to function. Examples include restaurants, shops, offices, private residences, hotels, and parking lots or garages.

Sources

These definitions borrow from the Conservation Law Foundation’s People’s Guide to the Public Waterfront Act.

Definitions for Construction Styles

High-rise Concrete & Steel

Concrete and steel high-rise construction 12+ stories

Mid-rise Concrete Foundation

Mid-rise poured concrete foundation 5-12 stories

Low-rise Stick-built

Stick-built construction up to 5 stories

Crosswalk for Building Uses

If you are considering specialized or non-typical building uses, this “crosswalk” can help you decide how to define your building program using the uses included in this tool. Please keep in mind that the tool’s results are most credible when handling the non-specialized uses that are provided as defaults.

Specialized Use

Recommended Basic Land Use

Notes on Usage

- LabOfficeLab space typically rents at a premium to regular office space; tool results may slightly underestimate project value.

- Test Kitchen / Industrial KitchenIndustrialN/A

- Self-StorageIndustrialSelf-storage typically rents at a premium to other industrial space; tool results may slightly underestimate project value.

- ShowroomIndustrial or RetailExperiential spaces designed to showcase manufacturing products to customers; may include hybrid retail or industrial elements.

- Flex SpaceIndustrialSpaces that combine elements of office and industrial uses. Typically rents at a premium to other industrial space; tool results may slightly underestimate project value.

The tool is not designed to evaluate other specialized uses such as educational facilities, health and fitness facilities, hospitals, museums, or entertainment venues. The tool is not designed to evaluate single-family homes.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the difference between the proposed project and the comparison project? What does it mean when one is more valuable than the other?

Definition of Proposed Project and Comparison project:

The calculator compares the scale and value of a proposed project with the scale and value of a comparison project:

- Your proposed project can be any project with a specified real estate program (e.g. 50% rental housing and 50% condominium housing). It can be a real project being contemplated in your community, or any other project that you come up with independently.

- The comparison project represents the legally achievable scale of real estate development, given the site conditions you specify and given the set of Public Waterfront Act legal requirements that are in force. The comparison project shares the same proportional mix of real estate uses (e.g. 50% rental housing and 50% condominium housing) as the proposed project.

Interpreting the difference between the proposed project and the comparison project:

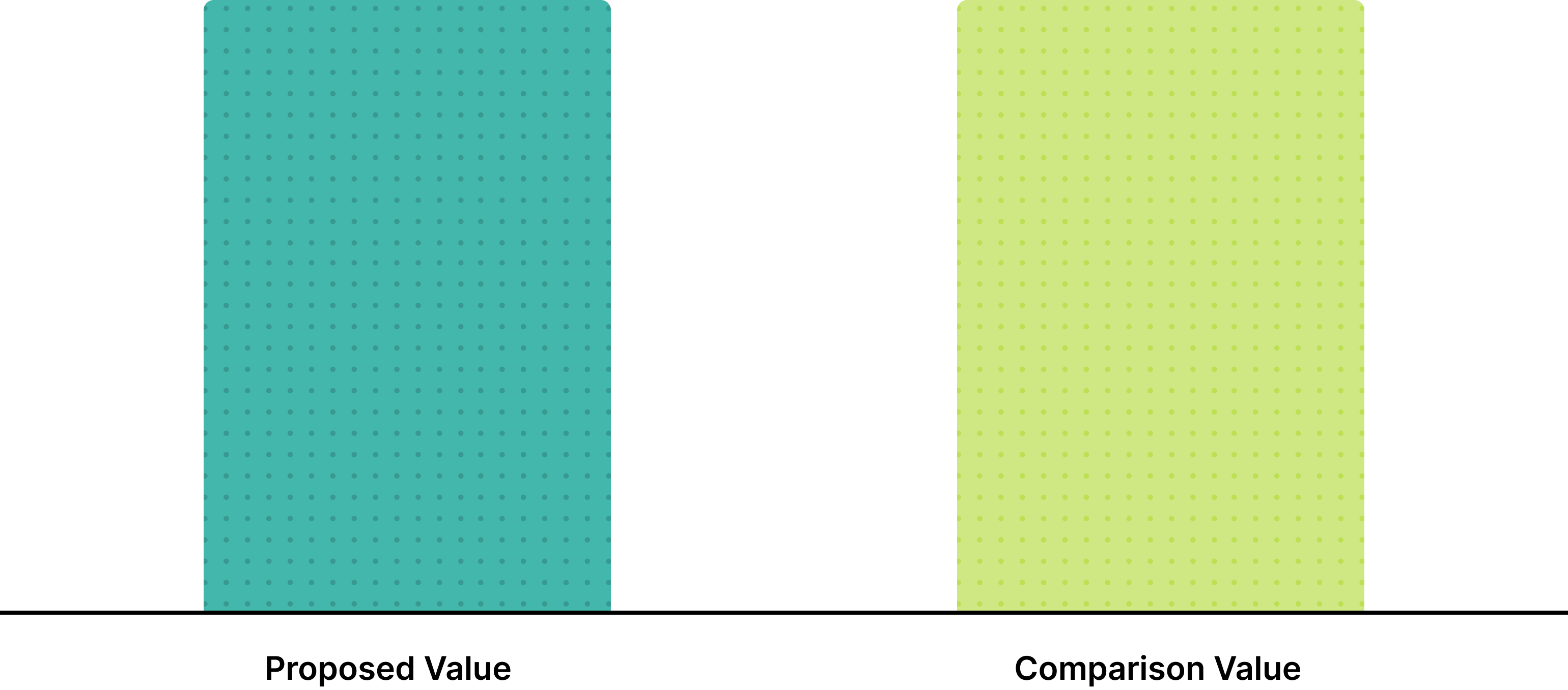

Scenario 1. The scope and estimated land value of the proposed and comparison projects are about the same.

In this scenario, the proposed project aligns with public access requirements onsite. This could be because the proposed project already abides by default Public Waterfront Act requirements.

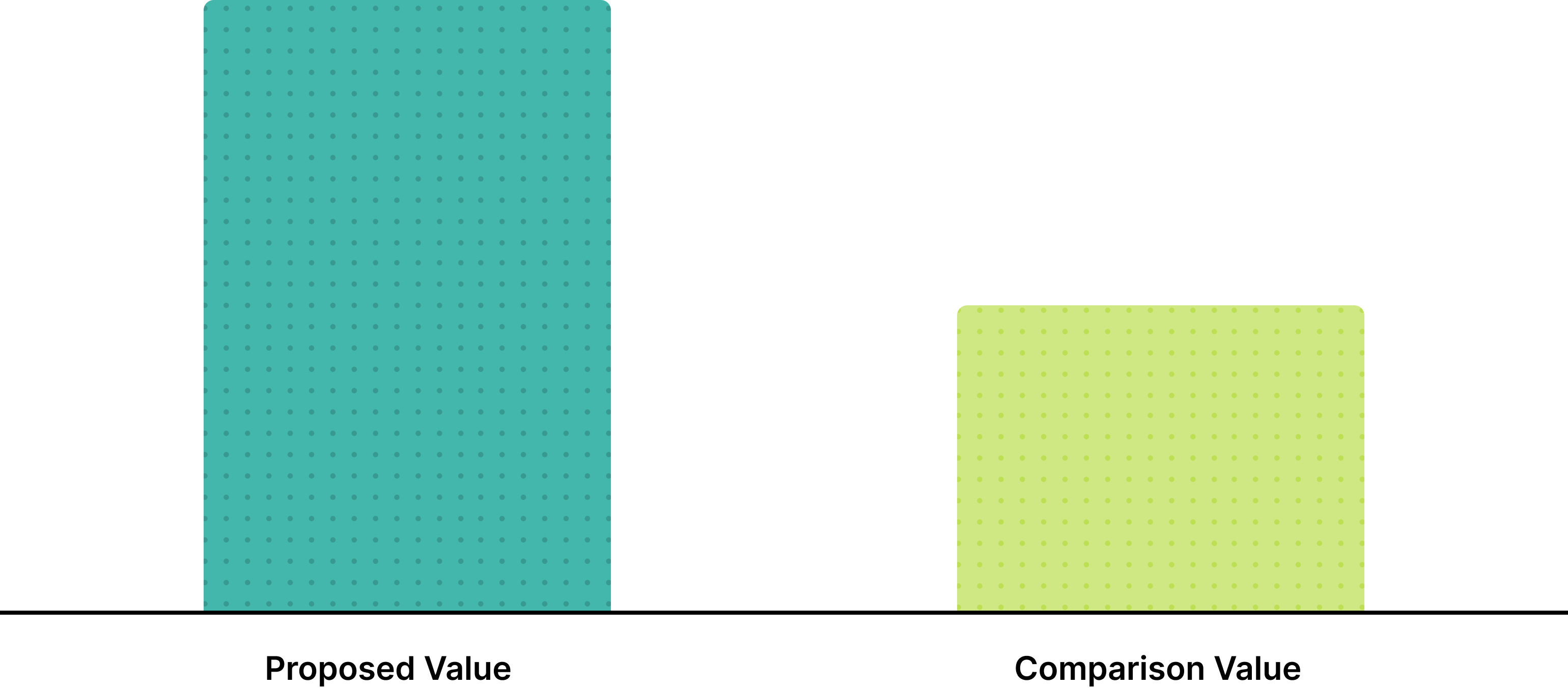

Scenario 2. The scope and estimated land value of the proposed and comparison projects exceeds that of the comparison project.

In this scenario, the proposed project is larger or otherwise more valuable than the comparison project, given the specific set of Public Waterfront Act requirements that are governing the comparison project. The project owner’s proposal likely exceeds what is permissible on the site.

This scenario is more likely in dense urban markets such as Boston and surrounding communities, where waterfront land is highly valuable and developers are therefore more likely to attempt to maximize the dimensions of a project.

In this scenario, there are two options:

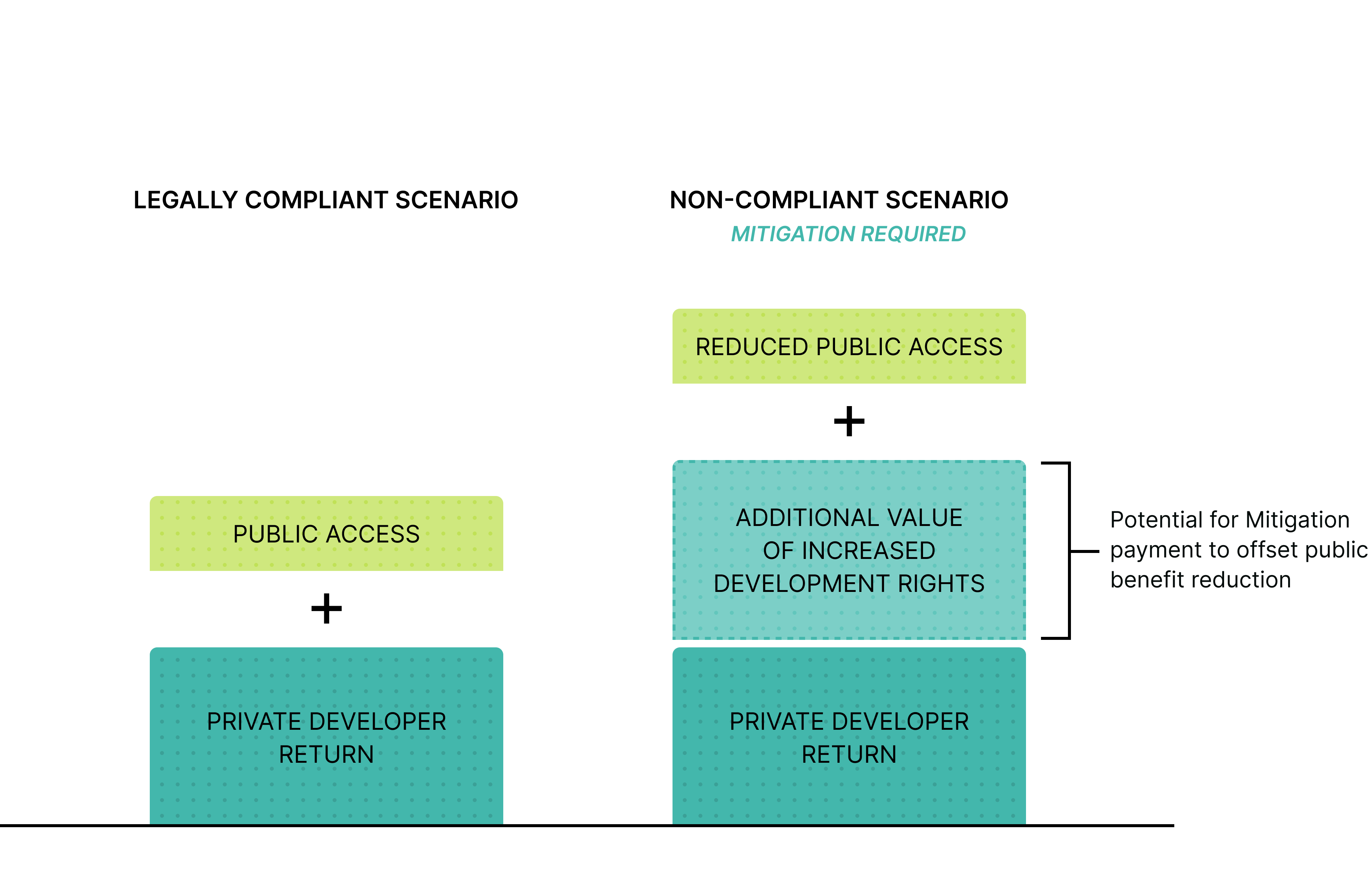

- Build as is, possibly in exchange for compensation. The proposed project is benefiting from the relaxation of certain Public Waterfront Act requirements and thus the reduction in public access onsite. If the project owner is unable to offset these reductions with onsite public benefits (e.g. by preserving public access another way, delivering public-serving infrastructure that expands access to the waterfront, etc.), then the project owner must compensate the public for reducing their legal access rights. This compensation is also known as “financial mitigation.”

- Revise the proposal to make it compliant. Scale down the proposed real estate program to adhere to public access requirements. For instance, reducing the footprint of the building so that 50% of the site is open space would force the project to align to Act requirements.

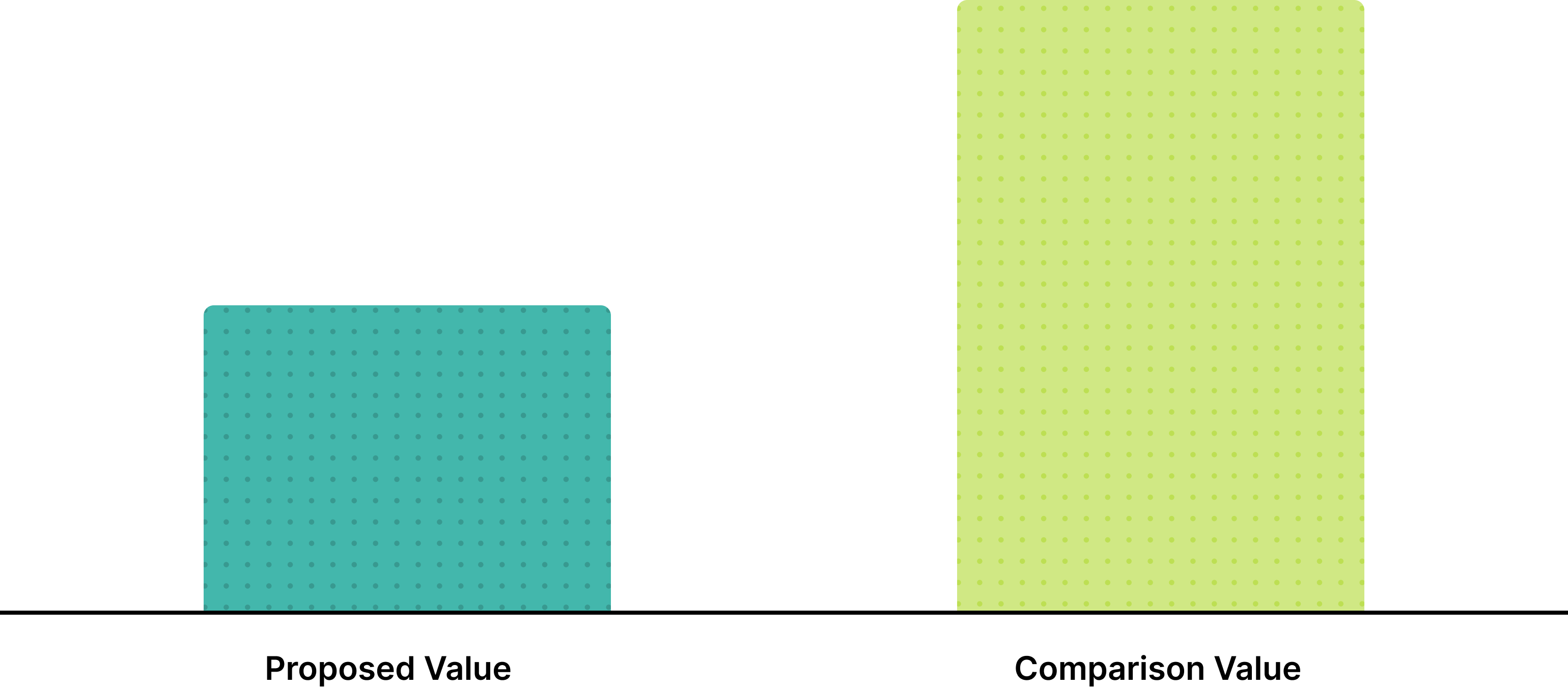

The scope and estimated land value of the proposed project is less than that of the comparison project.

In this scenario, the proposed project is smaller in scale or value than what is achievable given the conditions of the site and the specific set of Public Waterfront Act requirements that are legally in force. No offsets or financial mitigation is needed, since public waterfront access rights likely remain protected.

This scenario is more likely on especially large development sites, or in areas where market conditions are not strong enough to support building out to the maximum height or scale allowed onsite. It may not make sense financially to maximize buildable area onsite, which suggests that there is little incentive to impose on public waterfront access rights.

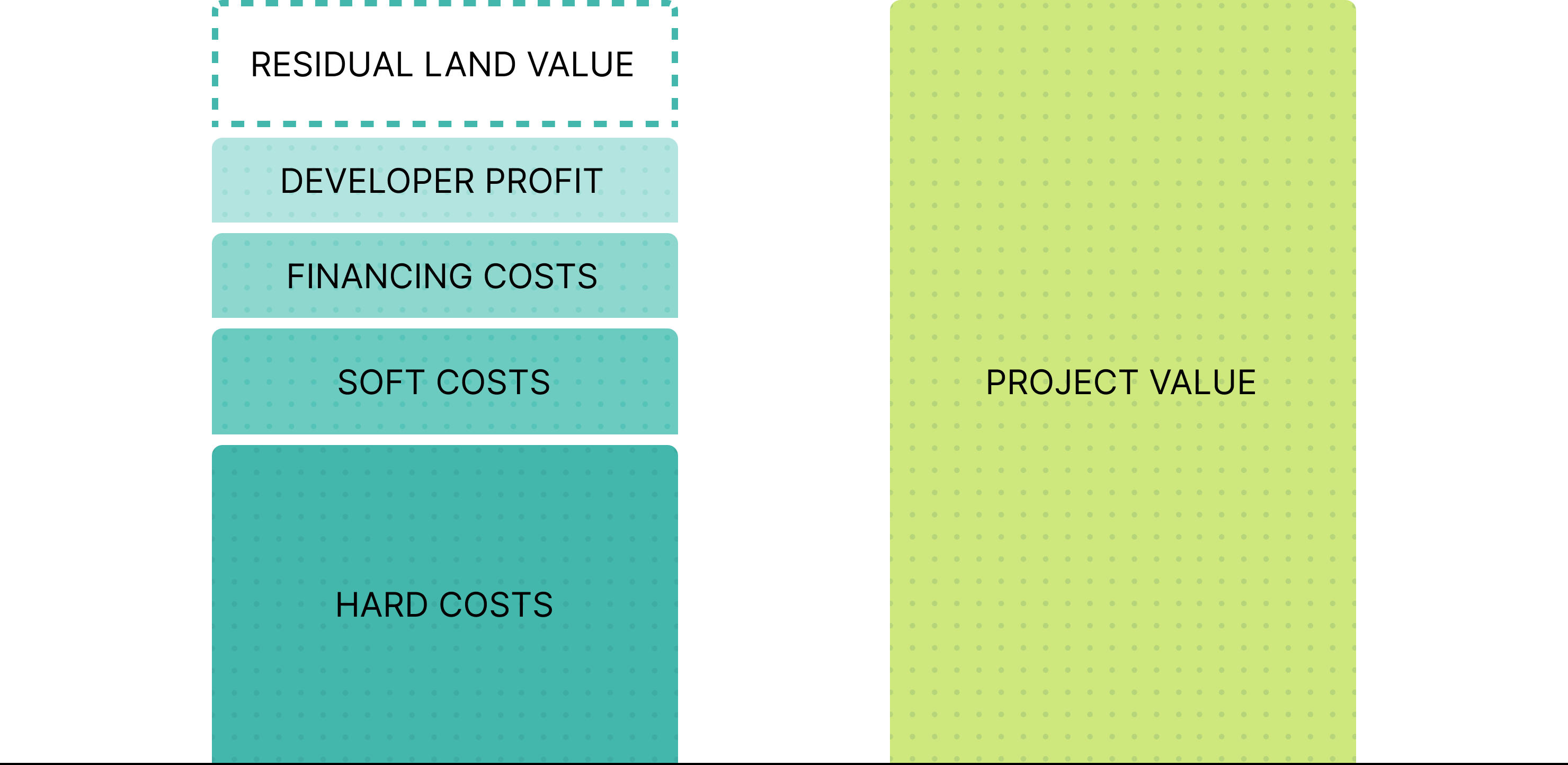

What is Residual Land Value? What is the Land Value Premium?

When this [calculator] discusses “value,” it is referring to residual land value. Residual land valuation is a widely accepted method for estimating the value of property or development rights that are attached to a property. The residual land value (RLV) of a project is equal to the total value of a given development program minus hard and soft development costs, financing costs, and the developer’s required profit.*

In other words, the residual land value is the residual sum available for buying the land—the most a developer can spend on the land while still meeting a minimum required return.

Residual land value depends on the development planned for a site. The more valuable a given development program, the greater the amount the developer can afford to spend on the land and therefore the greater the residual land value. It follows that relaxing Public Waterfront Act requirements can enable a greater scale of development onsite, which can increase residual land value.

By reducing or eliminating certain Public Waterfront Act requirements, you can quantify the change in estimated residual land value that results. This change in value is the land value premium unlocked by relaxing Public Waterfront Act requirements in the context of a municipal harbor plan.

A substantial land value premium could be a source of compensation to the public, if a developer that secures substitutions to Public Waterfront Act requirements also cannot avoid a net reduction to public waterfront access onsite.

*Developer profit: The model measures developer profit as a rate of return, and it assumes the amount of money available to purchase land does not reduce the developer’s internal rate of return (IRR) below the industry standard of 15% for most uses and 18% for condominiums.

The land value premium is not the same as developer profit. In theory, the developer achieves at least the same IRR on the additional development unlocked by reducing public access requirements. However, if the marginal cost of building that additional development is less than the marginal benefit to the developer (in terms of additional revenues and sale value over time), then developer profit will increase thanks to the legal changes.